Biological Recording and Learning

Biological Recording and Learning

Exploring the sense of progress as an ecologist

It is no surprise to anyone that knows me that I have become fascinated by oceanic bryophytes over the past year. I started this journey on a whim in October 2023, having come across my first oceanic liverwort, the Prickly Featherwort (Plagiochila spinulosa) in Ravensdale Forest Park, Co. Louth. Over much of the Winter that followed and early Spring (plus this side of the Summer of 2024), I have been steadily improving my identification skills in bryophytes. My learning has gone beyond ID characteristics, their ecology, their physiology, their evolutionary biology – it has been so fascinating. I think the most amazing thing I discovered was in the evolution of ferns and bryophytes. Hornworts are not very diverse in Ireland (I have never seen one), but I recently learnt that one of their photoreceptor proteins (the compounds which allow for photosynthesis) is believed to have been co-opted by ferns via a process known as horizontal gene transfer (Li et al., 2014). This is very common in unicellular bacteria, but very rare in eukaryotic life. This photoreceptor which is found in both ferns and hornworts allows for enhanced photosynthesis activity in low-light situations, which bryophytes and ferns are often found. This blew my mind.

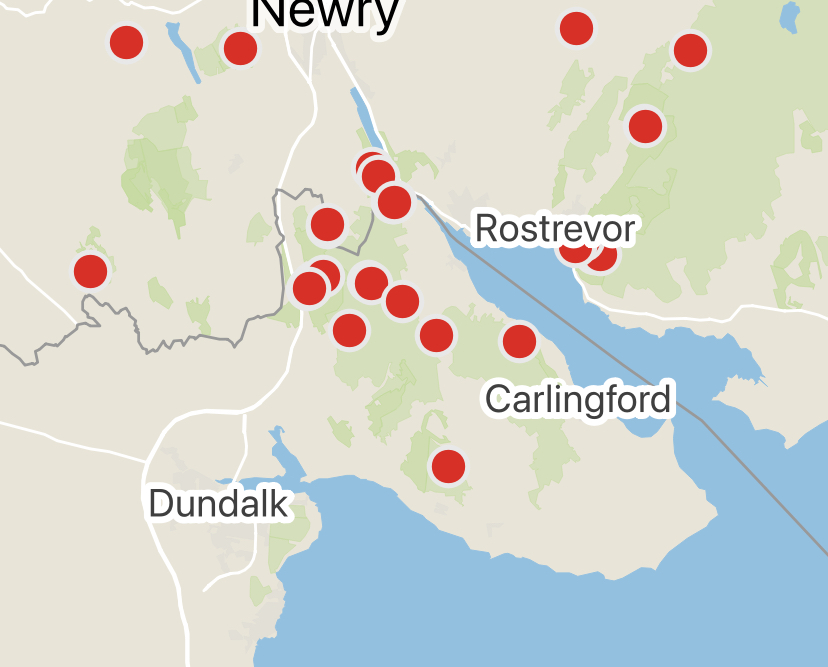

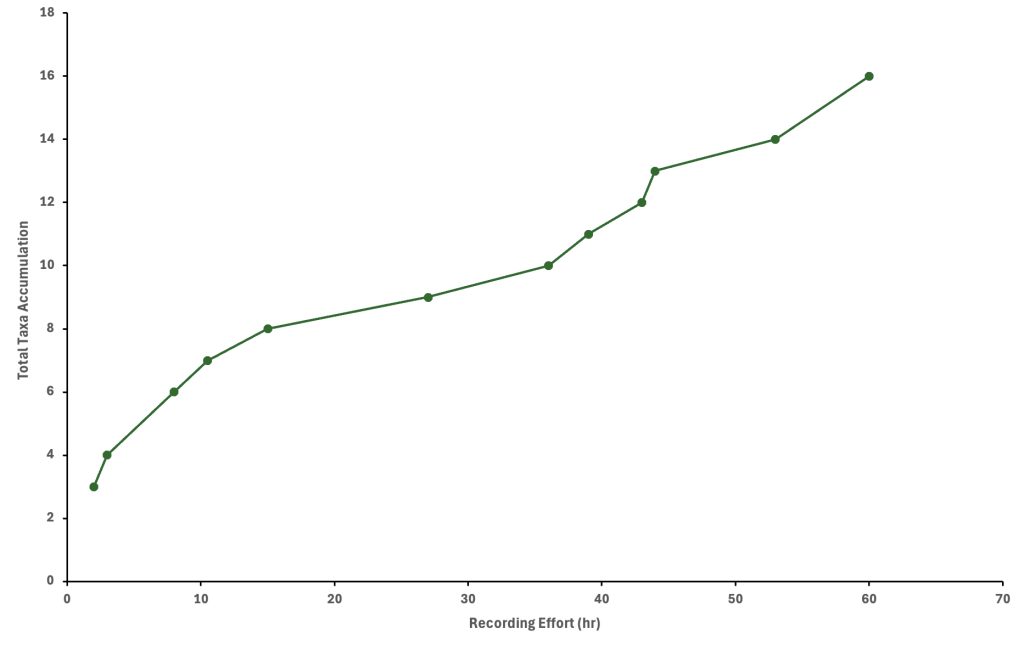

Anyway, it is through this journey, wherein, I have been collating my oceanic bryophyte records and placing them on a map, that I have been thinking about progress and how it is not only relative, but entirely dependent on the taxa you study. Most of my records have come from Cooley and the southern end of the Ring of Gullion, but this is an observational bias and not necessarily a natural distribution trend. My efforts have been concentrated largely on ravines and glens, and a large part of this involves looking at satellite imagery and finding what appears to be good habitat for certain species – otherwise known as field skills. A friend of mine made the suggestion to plot the amount of species recorded by recording effort (graph below). It is here, that I realised that oceanic bryophytes are particularly slow progress. There are many reasons for this, but the main one is simply the amount of time one can spend and not find anything, despite suitable habitat. Over the past 14 months, I have recorded 16 oceanic-montane bryophyte species and two oceanic fern species across approximately 60 hours of recording effort. Slow going compared to flowering plants or flies.

However, I am okay with this. It’s a learning process, and one which I have thoroughly enjoyed. Finding these overlooked and undervalued organisms has taken me to lovely places where you can think and ponder about all sorts of things. There are many target species I still wish to see. There are several very old records from the Mournes of hyper-oceanic bryophytes which I endeavour to find (or at least try). We have lost so much, but it is in this process of loss that we learn what has been there the entire time, unnoticed and unloved.

A map of my records in SE Ulster and a plot of recording effort in finding them!

References

Li, F.W., Villarreal, J.C., Kelly, S., Rothfels, C.J., Melkonian, M., Frangedakis, E., Ruhsam, M., Sigel, E.M., Der, J.P., Pittermann, J. and Burge, D.O., 2014. Horizontal transfer of an adaptive chimeric photoreceptor from bryophytes to ferns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(18), pp.6672-6677.